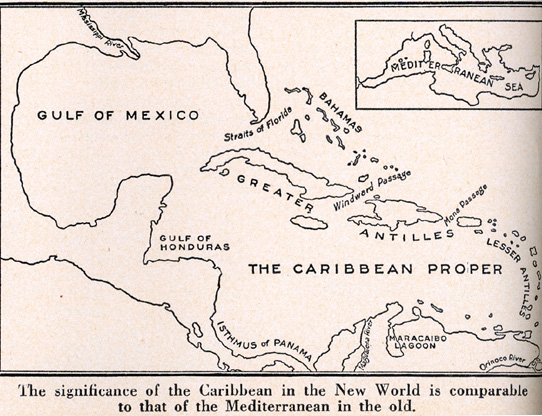

Southern historians have often been preoccupied with the distinctiveness of the United States South. Book after book and article after article have stressed the uniqueness of “the South,” not just from the rest of the United States, but from the rest of the world. In many ways, the South’s distinctiveness has manifested itself throughout the historical profession. We have the Southern Historical Association, the Journal of Southern History, and many schools offer a Ph.D. exam field in “southern history.” Put a different way, many historians have treated the American South as a place apart from the rest. Matthew Pratt Guterl’s American Mediterranean: Southern Slaveholders in the Age of Emancipation (2008), however, makes a compelling case against southern distinctiveness. Instead, he suggests, “We need to refocus our energies on the far-reaching ‘hemispheric engagements’” that shaped the nineteenth-century American South (7). More specifically, Guterl examines several southern elite cosmopolitan slaveholders (which he calls the “master class”) to demonstrate that the fate of American slavery “was closely intertwined with the fate of slavery elsewhere in the Americas” (6). Southern elite slaveholders did not just see themselves as part of the United States (and later the Confederacy), but also as part of the “American Mediterranean,” a group of islands surrounding the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean (12).

Southern slaveholders, according to Guterl, could and did transcend the cultural and social divides between the United States, the Caribbean, and Latin America. These elites approached African slavery from a “universal perspective” and assumed what happened to slaveholders in other parts of the American Mediterranean could easily happen to them. By the 1850s, Guterl argues, southern elites feared slavery was in mortal peril throughout the Americas. Threatened by a growing number of emancipations, slave rebellions, and antislavery movements, these slaveholders viewed the American Mediterranean “with a mixture of fear and excitement” (33). Cuba was the main source of Southern enthusiasm (many believed the annexation of Cuba as a slave territory was forthcoming), while Haiti served as a stark reminder for slaveholders about the dangers of slave revolution.

Although southern slave states saw themselves as part of the American Mediterranean, their appeal to “the revolutionary republican tradition, their lust for Caribbean territory, and the location of the South in a Pan-American context” led them to identify the southern United States as the “superior civilization in a singular, maritime system of economic, social and cultural exchange” (49). Moreover, secession from the Union and the establishment of the Confederacy brought new light and air to this idea. Following the military defeat of the Confederacy, however, the role of the South in the American Mediterranean changed. The abolishment of slavery ended any chance of “southern expansion into the Caribbean” and drew the region under tighter control and supervision by the federal government (49).

During Reconstruction, many slaveholders wrestled with the idea of relocating to Brazil, Cuba, Venezuela, or Mexico. “A sense of dislocation, diaspora, and exile,” Guterl argues, “settled across the depopulated and destroyed the South” (80). The slaveholder diaspora further demonstrates the close connections many slaveholders held with the larger American Mediterranean. The other option many slaveholders considered was remaining in the South and reestablishing pseudo-slavery through labor contracts and “black codes.” Guterl’s assessment of post-emancipation society in the South aligns nicely with other works on this period such as Seymour Drescher’s The Mighty Experiment, Rebecca Scott’s Degrees of Freedom, and Eric Foner’s Reconstruction.

Guterl concludes his study with a section on coolie and European immigrant labor in the American South. Guterl adds to growing list of scholarly works that highlight the post-emancipation South’s search for labor, which extended beyond freedmen and incorporates “the triangulation of white, black, and yellow labor within the context of ‘imperial labor relocation.’” (151). Like the rest of his work, this section clearly demonstrates that southern slaveholders were not constrained by the “borders of the Old South,” but were instead engaged with the outside world (185). Following the Civil War, southern sectionalism, more than ever before, was international.

Like all works of history, Guterl’s study has a few issues. Although the term “American Mediterranean” is provocative, it may cause some confusion for historians. Guterl defines the American Mediterranean as a “fraternity of slaveholders” around the islands in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean (1). Most of the Gulf Coast, however, was taken up by the republic of Mexico, which was antislavery and did not have slaveholders. Guterl does not explain this exception. The scale of periodization also tends to be important for world and global histories. Guterl, however, fails to mention when the American Mediterranean originated. With American Independence? With the independence of various Latin American countries? With the Cotton Revolution? Following the Haitian Revolution? More clarification on periodization is needed.

Furthermore, Guterl’ focus on southern elite slaveholders leads him to ignore small slaveholders (at least for the most part). As Peter Kolchin’s American Slavery (1994) has shown us, the majority of American slaveholders held fewer than 20 slaves. This raises the question: how and where did the average American slaveholders fit into this American Mediterranean paradigm? Furthermore, Guterl completely ignores the perspectives of Latin American slaveholders. Was this understanding of slavery and the American Mediterranean a one-way street, or was there a consensus among the master class and Latin American slaveowners? Finally, Guterl does not differentiate between societies with slaves and slave societies. Guterl’s American Mediterranean includes both types of societies, and more clarification on this differentiation would have helped further contextualize his argument.

Guterl’s study, in short, forces scholars to rethink the history of the Southern United States. Like Thomas Bender, Guterl takes issue with the limitations of examining United States history from the perspective of the nation-state. To make sense of American history, Bender and Guterl argue, historians need to look beyond the physical confines of the nation-state and towards the “hemisphere engagements” of race, class, gender. Doing so will provide a more globalized and transnational understanding of history. Moreover, Guterl’s study aligns nicely with Rosemarie Zagarri’s assessment of “American exceptionalism.” Guterl clearly points out that southern slavery was not a “peculiar institution,” but shared many qualities with other slave systems throughout the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean. I wish Guterl had pushed his study as far as Zagarri’s and considered the implications of southern slaveholding on the Old World and vice versa (especially in the East Indies). Guterl’s emphasis on transnational history and the implication of southern imperialism in the American Mediterranean also agrees with Paul Kramer’s essay “Power and Connection.” I would have liked Guterl to push his argument a bit further and describe how these different slaveholding societies influenced each other. Part of transnational history is not just showing an exchange of goods, people, and ideas, but also how these exchanges influenced the development of society.

Matthew Pratt Guterl’s American Mediterranean provides an important contribution to several historiographical fields. Although many historians of southern history have focused on the South’s distinctiveness, Guterl clearly shows that southern sectionalism was actually a part of a larger international world. This historiographical interjection is critical to understanding of southern history, United States history, and world history. American Mediterranean, in short, is essential reading for any history student.